Speaker

Dr. Chao-shiuan Liu,

WDSI Project Manager

Chairman, Foundation of Chinese Culture for Sustainable Development

The global human population in the 18th century, at the time of the Industrial Revolution, reached just 1 billion. By the 21st century, it was 7.5 billion. Meanwhile, atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide increased from 280ppm in the 18th century to 400ppm in the 21st century, and continues the upward trend. In geological time scale, the epoch succeeding the Pleistocene up to the time of modern day civilization is called the Holocene. However, human activities have since come to dominate the planet’s environment, and scientists propose that this new period should be called the age of the Anthropocene.

The 19th century was the height of colonialism, and there are nations you probably can’t even imagine being colonizers. There is Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Belgium, and even Denmark, Austria-Hungary, Russia, the Ottoman Empire (modern day Turkey), the US, and Japan. At its zenith, the British Empire took over a fifth of the world’s land mass, hence earning the extravagant name of "the empire on which the sun never sets" is extravagant. Its colonies included lands across Asia, Africa, Europe, the Americas, Australasia, and even island nations in the Pacific, the Atlantic, and the Antarctic. The 19th century is the pinnacle of colonialism.

The 20th century was a justifiably accomplished era with unprecedented technological, financial, economic, and social advances, bringing new impact on life and generally, change for the better. Unfortunately, it is also beset with war. From early 20th century, there are over 150 conflicts involving 10,000 people or more, including the Eight-Nation Alliance against China, Russo-Japanese War, Italo-Turkish War, Balkan Wars, First and Second World Wars, Korean War, Vietnam War, and the countless wars in the Middle East, South America, and Africa. Casualties amounted to almost 1 billion souls. It is a history filled with horrors too bitter to retrace.

The wars of the 21st century has developed into new forms of trade wars, financial wars, cyber warfare, and terrorism. The increasing human population and injudicious use of technology created environmental destruction, global climate change, exhaustion of natural resources, and economic inequality. These are some of the most pressing matters confronting us at the beginning of the 21st century. From a political point of view, the global power structure is shifting from unilateral to bilateral and even to multilateral extremism. The current western structure of global governance is hanging by its threads, imminent in its failure. Furthermore, the changing faces of technology and revolutions in artificial intelligence and genetic engineering pose great challenges to the intellectual and biological underpinnings of humankind, questioning established moral and ethical ideals. Many are asking, is human civilization sustainable?

With this in mind, the UN published《Our Common Future》in 1988, led by former Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland, It pioneered the concept of sustainable development as being “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” Subsequently, sustainable development introduced the 3 important pillars of Economic Development, Social Justice, and Environmental Protection, that is to achieve a balance between the economic, the social, and the environmental.

In the past 20 to 30 years, advanced countries have made remarkable progress in areas of Economic Development and Environmental Protection, but achieved little in the way of Social Justice. We are referring to Social Justice on the level of international society, not just in the domestic space. There are even signs of regression in our push for sustainable development, so experts have argued there should be a fourth pillar, that of culture. But culture isn’t a fourth pillar. It’s the base which forms the support for the 3 pillars.

Historian Arnold Toynbee finds many similarities between 20th century society and the Warring States period in China, and proposes that the dilemmas of 21st century human civilization be tackled with classical ideas from Confucianism and Mahayana Buddhism. His views are a clue to how Chinese culture may contribute to the chaotic world of today. Let’s look closer at his observations. Confucian culture emanates from the center, with cultivation of the self, ordering of the family, governance of the nation, to bringing peace to all under the heaven. “Under the heaven” is a concept that shows ultimate concern for all humankind, which is rarely mentioned in other cultures, especially in the west.

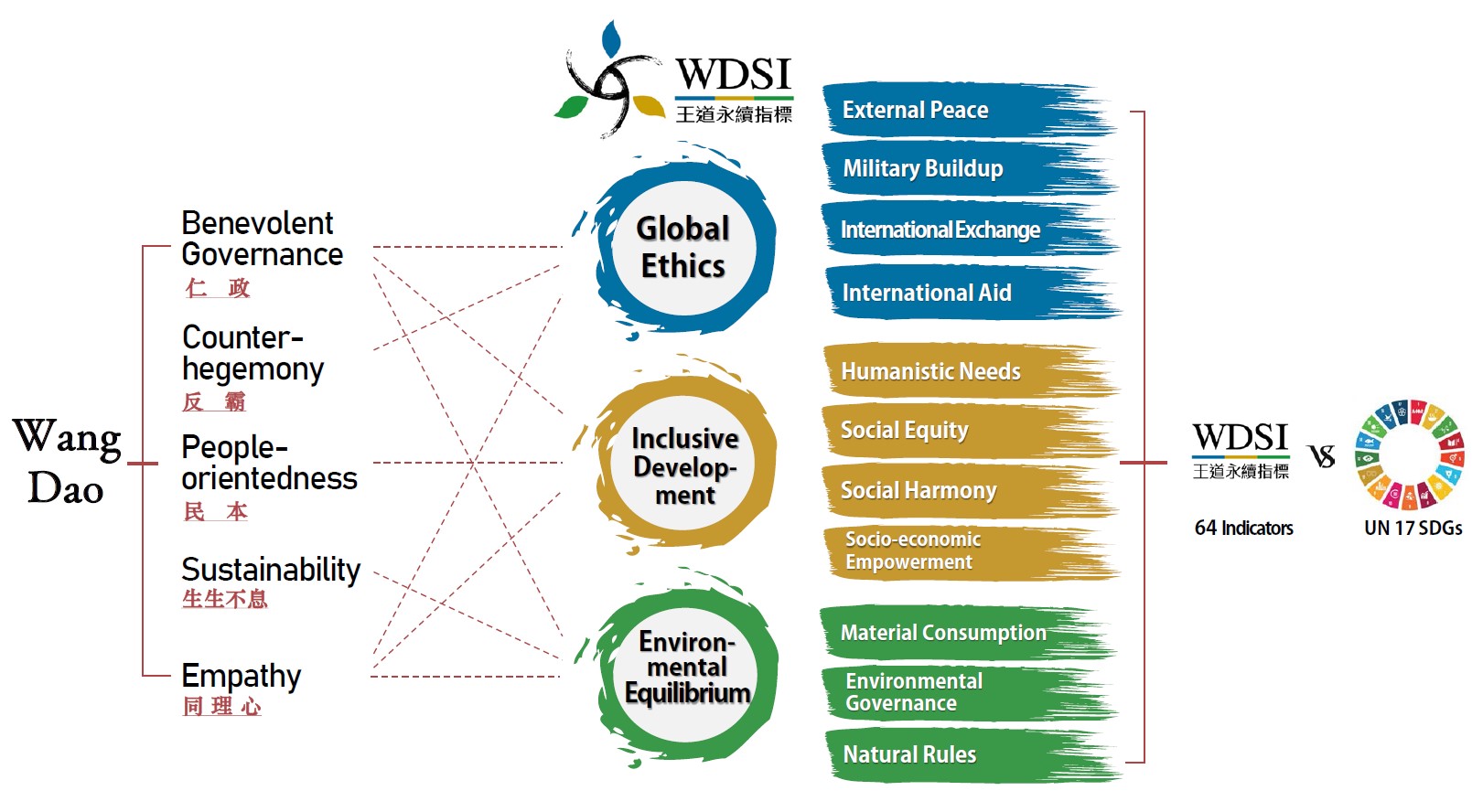

We represent Confucianism in Chinese culture with the precept of Wang Dao. In Wang Dao, we propose 5 essential elements: Benevolent governance, Counterhegemony, People-orientedness, Sustainability, and Empathy. Of the 5 elements, I personally believe Benevolent governance and Empathy are key. Benevolent governance is showing benevolence, while Empathy is to put yourself in other’s position, in one word, reciprocity. Both are the fundamental principles of Confucianism. Combining these 2 essential elements with the other 3 brought us some interesting results.

Benevolent governance and Empathy, combined with Counterhegemony, can define a new domain of Global Ethics. Benevolent governance and Empathy, combined with People-orientedness, is the popularly discussed topic of Inclusive Development. Benevolent governance and Empathy, combined with Sustainability, begets Environmental Equilibrium. In other words, Wang Dao is the way (Dao) connecting people with people, nation with nation, and humankind with nature. The domains of Global Ethics, Inclusive Development, and Environmental Equilibrium neatly correspond with the 3 pillars of sustainable development. Next, we needed to develop a workable mechanism to go beyond the discourse phase. That mechanism, or framework, is the creation of the Wang Dao Sustainability Index.

How does this Index differ from other sustainable development indices? First, none of them emphasize Global Ethics. Not long ago, one friend, a professor from the US, had a discussion about Syria. He had said that Syria is not a free country. I offered sarcastically, “Of course it’s free. It’s free to bomb the country.” In a country like Syria, no matter which index you measure it by, the economic and environmental ruin that it is, you’ll be hard pressed to find any progress. I feel we must take the impacts of war into account in some form of measure. So in our Index, the first thing we consider is Global Ethics.”

The goal of the second domain, Inclusive Development, is to incorporate 2 of the 3 pillars of sustainable development: economic development and social justice. In effect this is to take into consideration both growth and distribution, hence Inclusive Development, while leaving room for Global Ethics to play its part.

As to the domain of Environmental Equilibrium, it also differs from existing indices, such as the well known environmental index EPI (Environmental Performance Index), which emphasizes legislative policy and environmental management practices. Besides enforcement of policy, the WDSI stresses material consumption. We believe our goal of sustainability is not reachable without considering the effects of consumption. The true goal of sustainability is to think about the needs of our next generation, which is why when consumption is taken into account, the rankings of nations shifted dramatically from its EPI standing versus the WDSI rankings.

Almost concurrently, in 2016, the UN released its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which includes “No Poverty”, “Zero Hunger”, “Good Health and Well-being”, “Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions”, “Life on Land”, and more. 110 Indicators were derived from these goals, forming what is known as the Sustainable Development Goals Index (SDGI). Coincidentally, in parallel to their endeavor, we were laying down the WDSI. There are obvious analogues between the SDGI and WDSI, and we can compare the two using correlation coefficients. The initial sample batch of the WDSI consists of 74 countries, while the SDGI’s covers 156 countries. Our findings show an overall correlation coefficient value of 0.9, but developing countries are the outliers on the scatterplot, revealing the differences between the WDSI and SDGI.